By Deborah O’Donoghue, public affairs specialist, FSA Public Affairs Branch

On May 15, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law a piece of legislation that established the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It was the beginning of what Lincoln penned the “People’s Department.” A few years later, one of those people wrote in a journal:

June 5, 1875 — “Bought 16 bushel of rye from Henry Philipi paid him $20.00 for it.”

That person was my great-grandfather David Reynolds who lived in Jefferson County, Pa., just a stone’s throw from where Interstate 80 now runs. He was the son of Woodward Reynolds, the founder of Reynoldsville, Pa. If you’re unfamiliar with Reynoldsville, it’s near Emerickville, Prescottville, Sykesville, Brookville and Roseville. All of these ‘villes bunched together are about 75 miles northeast of Pittsburgh.

David was born in 1838 and died in 1916, leaving more than 30 years of journals that have been passed down through three generations of my family. Each journal chronicled his daily life, giving insight to everything from farming…

June 22, 1875 — “The rain was very much wanted as the crops was standing still for want of it.”

To politics…

June 30, 1875 — “The President and other high officials in Reynoldsville this afternoon selecting a site for a depot. A lively interest taken by the citizens.”

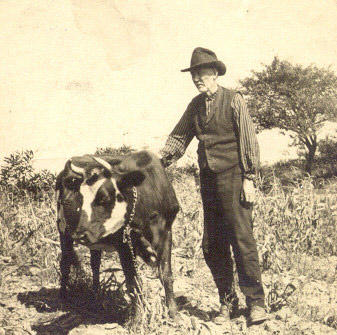

Farming has changed quite a bit since David Reynolds’ 1875 diary entries. He plowed fields using a horse, or if no horse was available, he hitched his cow to the plow. He didn’t have insecticides and fertilizers were all natural.

December 15, 1875 — “Finished hauling the manure bought from Stokes and Leach there was 38 loads in all paid $12.00 for it. Cheap enough.”

Based on the diary entries, David never interacted with USDA. The first county agent for USDA did not arrive in Pennsylvania until 1910 and was located in Bedford County, about 100 miles southeast of his farm. His family weathered the highs and the lows on their own and paid only for the necessities.

Oct. 12, 1875 — “Sold Robt. Miles ten bushels wheat at $1.25 per bul took it to mill for him.”

Great-granddad worked hard to produce those 10 bushels that earned him $12.50 and he provided free delivery. He noted in the diary that the wheat harvest began on July 12 and ended on July 16 with him and two men working the fields. On July 13 a lot of it was destroyed.

July 13, 1875 — “Severe storm of wind and rain this afternoon blew down nearly all the wheat we had shocked about a hundred doz.”

After losing his home and out buildings in a fire that destroyed about half of Reynoldsville on August 29, 1875. (he saved the “pianna,” his diaries and a few other items) he began a gradual recovery.

Sept. 24, 1875 — “Gave George Bliss check on Oyster for $9.00 in full for a hog bought after the fire.”

Oyster & Co. was the name of the bank and the $9 hog only lived until Nov. 16, when it was butchered to be cured for winter provisions to feed his wife and five kids (eventually the family would expand to 11 children).

Fast forward to the 21st century and that same hog at the New Holland, Pa. markets would sell for $48.00-50.00 per cwt for weights between 300-500 lbs and $51-53.50 per cwt for weights between 500-700 lbs, while boar hogs sell for $24.50-25.00 per cwt for weights between 300-700 lbs.

Livestock for the farm was no less important to my great-grandfather.

April 30, 1875 — “Dan Sharp found Old Muly Cow with a calf. Gave him $1 for it.”

Today, a Holstein bull calf weighing 95-115 lbs could sell for $190.00-$200.00 per hundredweight (cwt).

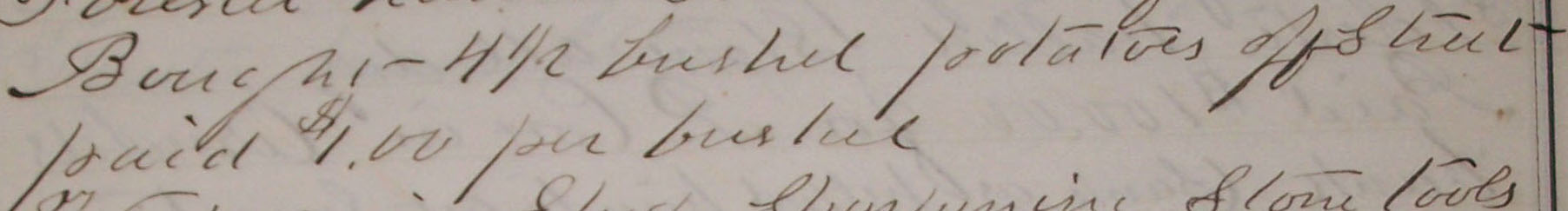

March 11, 1875 – “Bought 4 ½ bushel potatoes off Street paid $1.00 per bushel.”

He probably used these potatoes to seed for the coming summer. Using an old conversion chart from the 1945 Ag Census, a bushel of Irish potatoes was equal to 60 pounds, so great-granddad bought about 270 pounds of potatoes, or 2.7 hundredweight (cwt) in the standard measurement used today. He paid $4.00 for all those potatoes that today would cost $50 or more.

Great-grandfather David’s business diary is a treasured link to my ancestors. Although great-granddad David didn’t have access to the safety nets USDA provides for farmers and ranchers, it allows me to see and appreciate the work of USDA in general and the Farm Service Agency in particular. As the department celebrates 150 years, I can honestly say that I am proud to be the descendent of a Pennsylvania farmer and pleased to be a part of the “People’s Department.”

2 Responses to Journals Reveal Changes in Farming Since 1870s